Resistance to change is a normal human impulse. Even in the worst of circumstances, the familiar is often more comfortable than trying to rework a bad situation. When meaningful change does occur, as it has in Gloucester, Massachusetts, a small fishing town just shy of 30,000 residents, its impact resonates far beyond the borders of the intended target.

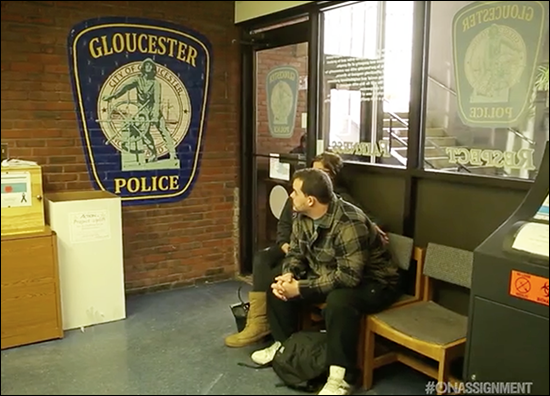

The Angel Initiative, founded by Gloucester Police Chief Leonard Campanello, in 2015, responded to the city’s plague of heroin and prescription painkiller overdoses in a new way. They stopped arresting addicts and instead offered to help them get treatment.

How Does the Angel Initiative Work?

“If an addict comes to the Gloucester Police Department and asks for help,” says the Gloucester PD website, “an officer will take them to the Addison Gilbert Hospital, where they will be paired with a volunteer “Angel” who will help guide them through the process. We have partnered with more than a dozen additional treatment centers to ensure that our patients receive the care and treatment they deserve – not in days or weeks, but immediately.”

The official statement goes on to note the following:

- Officers will dispose of any drugs and paraphernalia brought in

- No charges will be filed

- Participants will not be arrested

- There will be no jail time

In the law enforcement community, some see the Angel Initiative, which has helped an estimated 400 people get treatment, as an unprecedented approach to the epidemic of addiction. However, programs like this are part of the trend toward harm reduction policies that have grown out of what many feel is a failed war on drugs.

“It’s done. It’s over. It’s lost. It wasn’t a war on drugs. It was a war on addiction,” Chief Campanello said on NBC’s Dateline.

Though the Gloucester Police Department and its Angel Initiative are in the spotlight right now and deservedly so, other cities have adopted similar approaches. Santa Fe, New Mexico, Albany, New York, and Huntington, West Virginia have instituted Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion programs developed in Seattle, Washington five years ago.

Officers are allowed, under assisted diversion methods, to forego arresting drug offenders and instead funnel addicted individuals into programs that will address drug and alcohol dependency issues. Initial research on diversion tactics shows that cities are saving money and offenders are less likely to continue committing crimes.

An additional benefit to the harm-reducing techniques is the understanding within law enforcement circles that addiction is a chronic and often relapsing disease.

Those who volunteer or are referred to the Angel Initiative, for example, can receive medication assisted treatment (MAT), which helps to safely diminish cravings and the symptoms of withdrawal. Without MAT, many addicts are back on the streets seeking drugs within hours or days.

“If you’re going to accept it as a disease,” Chief Campanello tells NBC’s Josh Mankiewicz, “you’ve got to accept the relapse part of it. It’s not a perfect program. It’s a step toward treating the underlying cause of crime.”

Less than an hour from Boston, Gloucester will continue to face challenges with residents battling addiction. Yet, the city’s willingness to break ranks from the traditional war on drugs and offer compassion rather than handcuffs is the definition of meaningful change.

Watch the entire Dateline: On Assignment episode. Photos courtesy of NBC News.

Related:

Compassionate Policing: Mental Health and Law Enforcement Collaboration